A couple of months ago I decided to finally take the plunge and try self-hosting. In particular, I was sick of trying to find a Google Docs alternative, and sharing random CryptPads and Etherpads with academic collaborators seemed dodgy. I’d been interested in Nextcloud, but I’d been using a random provider through their marketplace, which didn’t seem too great, either. With the increase in AI cannibalism scraping-for-LLM-training, I wanted to move my documents to a place where I understood how they would be used. An E2E service didn’t quite work, since I wanted to be able to have people edit documents without needing an account on whatever service, and I needed it to appear semi-professional, at least.

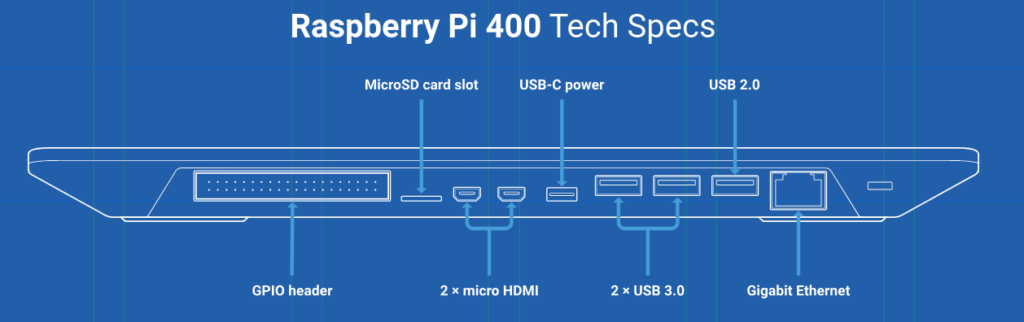

My approach has been one of relative low-tech; that is to say, I wanted to create relatively stable infrastructure that I could rely on and thus wanted reasonably well-developed infrastructure, rather that trying to do set up my own system entirely from scratch. I bought a used Raspberry Pi 400 (in a case — for convenient proximity to Ethernet connection, it’s housed next to the front door, aka lots of dust and dirt) on eBay for $40.

I booted it up with a fresh install of Raspberry Pi OS, once I secondarily purchased the micro HDMI converter I forgot I’d need 🤦♀️

I’d read about YunoHost and it seemed like one of the better options — free, open source, decent user community, and needed little to no custom software design. And indeed, setting up the OS itself wasn’t much of a problem. On the other hand, configuring my router to work with YunoHost and the Pi was much, much harder. I lost a few hours mucking around with Netgear Genie, I realized two things: 1) I should actually step back and learn some fundamentals of networking, and, 2) interesting networking projects should probably not be run off a who-knows-how-old router that has been inherited by multiple generations of tenants off contract.

That joyful learning experience aside (also with thanks to my flatmate for putting up with at least one complete firmware reset on the router), I got the thing up and running. Yay!

Now a couple months on, I’ve got a stable workflow with several apps I regularly use:

- Google Drive –> Nextcloud — whew, this one was not fun to configure. I usually use x86-64 hardware (along with an ARM-based PineBook Pro, the Pi is the only ARM64 hardware I’ve used) and in the process of setting up the Collabora server (which, reader, is a separate YunoHost application) EXCEPT if you’re using ARM, in which case you should use the Nextcloud add-on CODE server. I learned this the hard way, though I now see the app page for Collabora now imparts this rather handy knowledge.

- There’s one major bug I cannot figure out, however: when I create a new document on the web version of Nextcloud (as opposed to mounting Nextcloud as an external drive and creating a new file with a local word processor), I will always lose the first draft of what I write. I *think* this is some kind of sync error, wherein I’m failing to establish (.touch) the new document before I start writing to it. My current work-around is creating new documents via the word processor / external drive workflow and then editing from the web view, which is not ideal.

- I also cannot get the Zotero integration to work. While I’ve got the add-on installed, I cannot get it to load my entire library. Instead, I get maybe twenty or so entries, when I have 2,000 or so entries in my Zotero library. This is another reason why I keep returning to the local word processing.

- Todoist –> Vikunja — this is one of the rare times that I genuinely cannot find a solid FOSS replacement. I’m making Vikunja work, but it’s driving me a little batty. While I followed the steps to import my data from Todoist, I’m too used to Todoist’s sleek interface and miss the shorthand input (e.g., “repeat week” will set to auto-repeat weekly). Vikunja does have a setting to change the shorthand (I selected Todoist) but it’s not as sensitive — e.g. I rarely get the date format correct enough that it automatically assigns the desired completion date. I also wish there was a widget to add a new task from any page, rather than just the homepage. I do really appreciate the Teams feature and plan to use it at some point in the future — for now, my to-do list is feels too personal to open up the subdomain to any potential user (I know I can configure it to only users I’ve created, but still…)

- My meta-reflection on switching is that I hate how I completely fell prey to Todoist’s gamification of task completion. Somehow seeing the arbitrary five goals completed marker made me feel success in a way that merely checking off individual task in Vikunja does not. Of all the things to be gamified, maybe it’s good my to-do list is, though?

- Google Docs –> CryptPad — I had to give up on (well I’ve “paused” my instance, which is a great YunoHost feature) until I can figure out how to configure it such that only registered users can create new documents. This is a setting that exists for CryptPad more generally, but due to the way it is configured by default on YunoHost, it’s proving more tricky.

- ? –> Readeck — this is the one I didn’t realize I needed. Super easy to configure, Readeck is a place to save articles I want to (or should) read but haven’t gotten around to it yet. Removing these from my to-do list and instead putting them in a designed app is relieving some stress (from having a never-ending to-do list).

- Multiple proprietary URL archivers –> Archivebox — I worry a lot about bit rot, especially since I often want to archive things to return to for research. With Archivebox, I’m able to download the site in various forms (PDF, html, etc.). The site interface is clunky but the service is highly valuable — also because I sometimes save things I wouldn’t necessarily want to archive on a public site, where they might be subject to more

AI cannibalismweb crawling, e.g., someone’s creative work.

Overall, the static IP address finagling was worth it — I’m happy to have control over where my data is housed. Also, it’s been an interesting experience of coming to understand the material infrastructure of my house (a rental). I live in a fairly run-down neighborhood and our internet service, for example, reflects that — I was surprised when I was traveling for the summer and obviously away from the server how often our service was down. Given that I’m usually using my home network outside of regular working hours, issues that occur overnight or during those hours go unnoticed. That’s yet another reason we should all be in favor of expanded broadband access, etc., etc.