By last count, I’ve lived at six addresses in the United States, with varying degrees of permanence (I’ve been an official resident of one state the entire time, but had mailing addresses at five other locations, some in-state, some out, due to temporary jobs and schooling). So, when I recently went to fill out an update renter’s insurance application, in order to confirm my identity, I had to stare long and hard at the list of alleged prior addresses.

If you’re unfamiliar with this kind of verification system, institutions will contract with data brokers, who scrape public data (like voter registration or addresses on tax returns) and ask you to verify whether or not you’ve, for example, lived at any of the five prior addresses, or have ever owned a certain model of car. Making a mistake can send you into a long loop of escalated verification processes, some of which record your conversation with the customer service representative for “security and verification purposes”. I’m not a big fan of biometric data records and avoid them where possible, so I like to guess any prior addresses and car models correctly on the first try. However, there’s ambiguity in the questions themselves, given that I am perhaps not the default case. Having initially registered to vote, for example, at my parents’ address (I was completing high school at the time), I’ve definitely been “associated” with that address. But the question, as posed by my renter’s insurance firm, via their contracted data broker, is, “have you ever owned property” where one of the options is my parents’ address, where I have been registered. The crux of the problem is that I definitely didn’t own that property (as my parents would be quick to remind you, given my lack of contribution to their property taxes), but I don’t know if the data broker has effectively discerned that. Instead, all I know is that I, yes, have lived at that address. So I do what feels to be the reasonable thing — that is, I click “none of the above”.

Sure enough, I am immediately informed that my verification process has failed, which is deeply ironic, given that the data broker has actually misidentified me as a homeowner. I am then routed to a dreaded customer service interaction, where sure enough, I am given no option but to consent to my voice (as part of the entire conversation) being recorded, subject to a privacy policy “available on the firm’s website”. I need renter’s insurance, so I give in. Of course a lengthy wait time is required and I am forced to give a variety of identifying information, including my social security number, via audio call.

Reflecting later on the incident, it bothers me. Why did it fall to me to go out of my way to correct misleading (in fact, incorrect) data? Why are data brokers allowed to sell faulty systems that could lead, in fact, to false verification of identity? After some Web searches, I find out that there are a few key data brokerage firms in the US, including three big ones: Acxiom, Experian, and Epsilon. If there’s a category of business I hate to support more than credit report firms, there’s only the American tax return preparation services lobby…

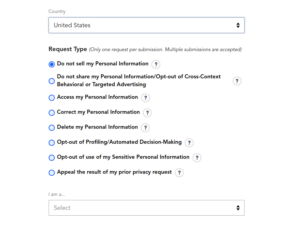

Now, I have a few options. First, I can request to have a copy of all my data pulled. There appear to be some options for correcting the data found on that report, but I have little to negative interest in giving these firms better records on me. Second, I can opt to have all my data deleted. Depending on the firm, there are additional options. No service (of the three aforementioned) will let me complete multiple steps at once, leading to 10-minute per brokerage firm submissions (and yes, I have to verify my identity to perform these tasks) for each desired goal, i.e. getting a copy of my report, and coming back later to request deletion.

Oh what fun! After about an hour of time, I submit three basic applications, to get a copy of “my” data (or data on the person these sites seem to think I am) from each of the three firms. I receive those reports each about a month after filling. The data inside those reports deserves a much longer post, but suffice it to say, there are plenty of errors. For example, my dad’s name shows up under one of my legal aliases. I’m pretty sure I know how it got there, as he’s listed as a legal custodian on my first bank account, and our motor vehicle registrations are intertwined.

I can easily imagine a situation where this quickly becomes a serious problem. For example, would my dad’s property ownership records then get mixed up with mine, since our “legal aliases” are? I suspect that’s exactly what happened to me in the case that launched this entire rambling post. This is yet another case of the fallacy of data as truth, and it makes me consider attempting to track down the personal phone number of the CEOs of these firms and deliver a message about the importance of personal privacy. But, unlike these firms, I respect personal privacy.

For the immediate now, I tell each firm (well, I take 10 minutes to submit a new privacy application, since opt-out culture is alive and thriving) they can’t use “my personal information”.

To see the effects, I try to open a new checking account a few weeks later, at a bank I know uses these data brokerage firms to verify customer identity. Sure enough, where I should hit a “just verify a few basic facts for us by selecting from the following…” page, I get an error code! They are unable to verify my identity at this time! I am always so happy to see when the most fundamental errors go unhandled — for example, an API request returning a “no one with that profile in our system”. I am instead given a phone number to call, and it is the general number for the bank. I am reconnected three or four times before I make it to someone who can actually verify my identity. Interestingly, they ask only for a recording of the call for security purposes, and insist that it will not be used for any marketing ones (do we believe them? I sniff a future class-action lawsuit.) It takes the representative a few minutes to verify my basic information, including social security number (which I could have typed online anyway), and then I am told a decision will be made in a few days. While I am never notified of a decision, a few days later I do receive login information for my shiny new checking account.

I’m not sure what the concrete results of my opting-out are yet. I know that it led to a long phone call and some honestly horrific hold music (banks should be ranked not by interest rate, but by hold music, hear me out), which isn’t ideal. At the same time, the information I had to provide this time was easy for me to provide since it was basic information that I, you know, am actually associated with. I am still curious how the final verification happened — was it even a full employee of the bank, or a contract worker? Who signed off on what disclosure of data? I was never asked to consent to any information sharing outside of the bank itself.

I am also aware that, besides burning some time that I should probably be using to do other things, I am yet to encounter the more concerning implications of refusal. For example, with these “informal” tenant screening tools used by plenty of landlords, if I have no profile, will that count against me? I guess time will tell, but I am not entirely optimistic. To future me, I do apologize, but it was for the best (I hope).

Notes:

I found the following site deeply helpful: https://privacyrights.org/data-brokers

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.